No one believed in offshore wind

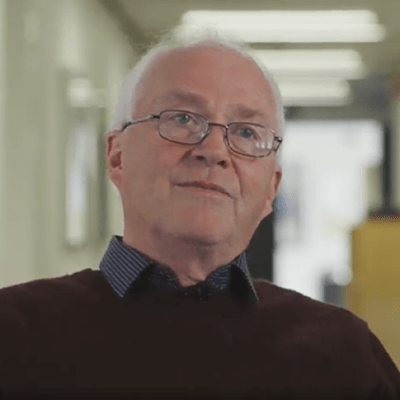

Peter Buhl sits behind his Ørsted desk in Skærbæk. He is a civil engineer specialising in offshore wind turbine foundations, in other words, how to design, dimension, and install the foundations to ensure that an offshore wind turbine remains firmly attached to the seabed year after year.

Peter’s first experience of offshore wind is as old as the technology itself because he helped build the world’s first offshore wind farm in 1990-1991:

– I worked on Vindeby, the offshore wind turbine project, I wasn’t green behind the ears, mind you, just an ordinary site engineer working on the design, casting, and placement of the foundations. This was the first time I’d ever worked on wind power or turbine foundations. My previous tasks had involved harbour construction – for quite a number of years, too.

Back then, Peter worked for the construction company Monberg &Thorsen, tasked with providing the foundations for Vindeby Offshore Wind Farm. The foundations were cast in concrete and placed on the seabed off the coast of Lolland, Denmark.

At that time, when Elkraft (later Ørsted) constructed Vindeby Offshore Wind Farm, offshore wind power was met with scepticism in the industry, Peter Buhl remembers. He readily admits that he didn’t see any future for offshore wind at first either:

– It was far too expensive and difficult for a variety of reasons, mainly because you can’t walk on water, making it hard to access the turbines and the foundations.

I fully agreed with everyone else: I didn’t believe it had much of a future.

Coal was king

In 1991, Denmark’s energy supply was marked by having struggled to recover from the oil crises of the 1970s. Among other things, the country had decided to switch to coal to replace oil for generating electricity.

The power generation changes were part of a policy shift to a multi-pronged energy supply, designed to increase Denmark’s reliability of supply by reducing its dependency on oil. In so doing, coal helped overcome an important societal challenge, as it was seen by many as a reliable source of electricity going forward.

But politicians also wanted to invest in renewable types of energy, such as wind power. As early as 1979, the Danish Parliament adopted a law to subsidise wind turbines and, in 1985, power companies were ordered to construct wind turbines to counteract the greenhouse effect and reduce carbon emissions.

To help achieve this aim, Denmark constructed the world’s first offshore wind farm off the coast near Vindeby.

Listen to Peter describe how he worked on the foundations and watch how they were installed on seabeds here.

Vindeby had to demonstrate the viability of offshore wind power

Vindeby Offshore Wind Farm needed to provide cold facts about offshore wind power’s potential to generate clean energy.

Many onshore wind turbines already existed, and the growing interest in trying to build wind farms at sea was initially based on the significantly higher winds offshore. It was predicted that one turbine could generate up to 50 % more electricity offshore than onshore. So because of the ample space in Denmark’s territorial waters, the theoretical potential was enormous.

But would it work in practice – and would it be financially viable?

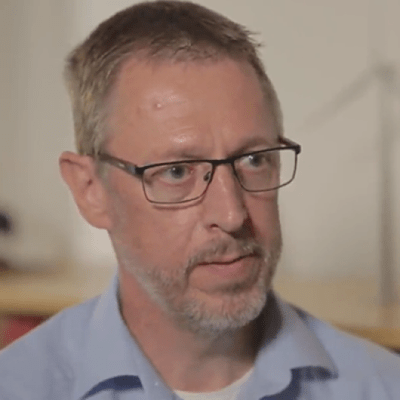

In 1991, Frank Olsen was head of department at Elkraft (now Ørsted) and he was tasked with constructing Vindeby Offshore Wind Farm. He remembers how the industry was keenly focused on the project, which intensified the pressure:

– Many of the turbines at the time had a number of operational weaknesses, and many had inferior gearboxes. If a turbine broke down on land, it could be fixed overnight, but it would take months before you could get out to Vindeby.

My biggest fear was having wind turbines out there breaking down one by one, and we couldn’t get out to them.

And then everyone could say: ‘Told you so! Wind turbines don’t work!’.

That’s why Frank and his colleagues working on Vindeby Offshore Wind Farm were eager to make it a high-quality project, technically speaking. It was a test of the technology’s viability.

Such a test was widely supported, too, among both the proponents and sceptics in the industry, says Frank:

– Wind power was driven by two primary forces: those who wanted to show that it was worthless and those who wanted to prove that it worked.

There were drawbacks. For instance, an offshore turbine is exposed to salt water and mists and has a higher risk of getting struck by lightning compared with onshore turbines. But Frank and his colleagues found solutions to these challenges, and Vindeby didn’t flop.

See how Frank and his colleagues addressed the challenges of putting turbines out at sea here.

Maintenance at sea

Morten Larsen was originally a qualified lorry mechanic, but changed careers and became a wind turbine technician. Vindeby was the first of many offshore wind farms he serviced, and a lot of new solutions had to be found to do this, because it was vastly different from maintaining onshore turbines where you could park your service vehicle at the base of the turbine.

Considering the high-tech solutions and service vessels that are currently part of a turbine technician’s daily work, it’s fascinating to hear Morten tell how he and his colleagues managed to do maintenance back then:

– We had to have a service van, of course, and we’d drive it to Onsevig on the coast. We knew an old man who’d rent out his fishing boat. His name was Bent.

We’d phone him at 6:30 in the morning and tell him that we had to sail out and service the turbines. When we got to Bent’s place, he’d already started the boat and heated up the bridge.

Bent sailed Morten and his colleague out to the turbines. Morten says that when the boat came up alongside a wind turbine, they climbed up a ladder onto the foundation, got all their tools moved over, and then they continued their climb up another ladder inside the turbine with a little more than 30 metres to the top. Then they had to pull up all their tools by hand before they could get to work:

– We had maybe 3 or 4 tool buckets, which couldn’t be too heavy because one of us had to pull them up a rope.

– No one ever needed to go to a fitness centre back then – we did all that at work.

Listen to Morten talk about life as a wind turbine technician at the world’s first offshore wind farm here.

Inconceivable developments in engineering science

Like Peter Buhl, Torben Poulsen is based at Ørsted’s Skærbæk office. Torben is a mechanical engineer and started his offshore career on the Vindeby turbines where he was tasked with finding any shortcomings before project completion.

Torben’s experiences from Vindeby and in the decades that followed give him keen insight into how the offshore wind industry has developed.

– My thoughts about Vindeby thirty years down the road are that it was thrilling to be a small part of, and that it helped drive developments in terms of the subsequent growth of offshore wind projects.

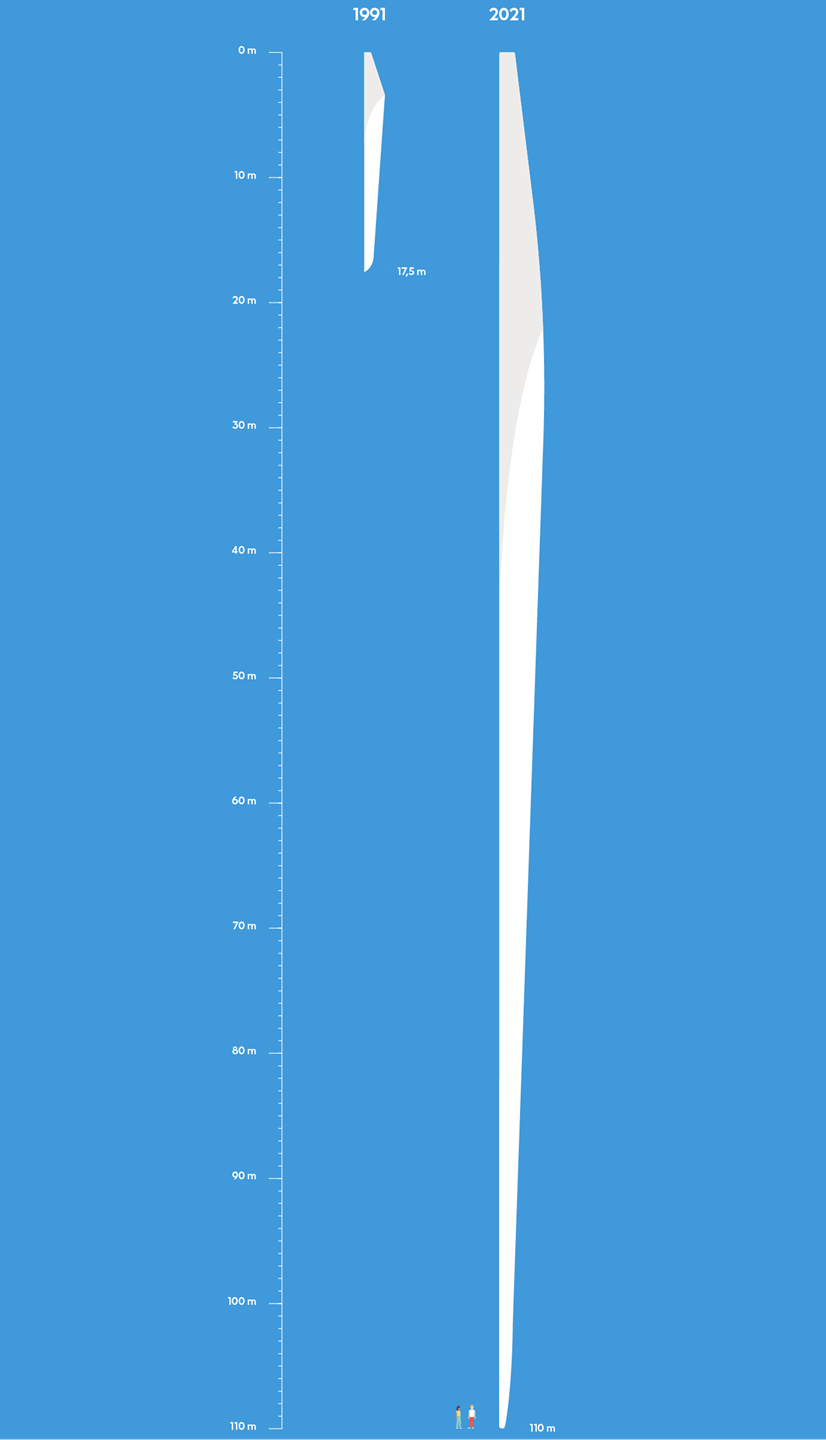

One recurring observation of the four offshore pioneers is the impressive pace at which offshore wind evolved after the first turbine blades started whirring thirty years ago.

Frank Olsen, who was in charge of constructing Vindeby Offshore Wind Farm at that time, had preferred having bigger turbines for the project than the 450 kW Bonus turbines. But they were the biggest, most reliable ones available. He says:

– It was inconceivable to me that they could ever get to be as big as 10–15 MW, but now it’s possible, largely by having completely different materials to work with.

Thirty years later, wind turbines generated roughly thirty times more power per turbine than those at Vindeby.

Peter Buhl explains:

– One step led to the development of the next of course. Engineering science has developed in terms of lifting equipment, vessels and the manufacture of concrete foundations, but also steel manufacturing in particular, which has become an enormous industry.

And it’s almost incomprehensible when you see what’s happened. None of us ever imagined that we would get to where we are today!

But it was also because we did something that no one thought was possible, right?

Watch Frank, Peter, Torben and Morten describe the developments that have taken place since Vindeby.

Watch more from the pioneers who made offshore wind a reality.